Last month, the Acton 250 Committee again welcomed Acton resident and historian Dr. Mary Fuhrer to Town Hall to bring her research and insight to Crown Resistance Day, Oct. 3, 1774.

The talk focused primarily on Acton, with some commentary on its nearby neighbors in the context of dictums coming from the King in London, and the actions and reactions by Boston and Salem, as the larger cities within Massachusetts.

Fuhrer laid out her talk as if there were a six legged stool or table in support of the Crown. Each event that shifted Acton (and similar towns) away from England pulled a leg from that stool, bringing it closer to collapse. She also noted, importantly, that to “Resist the Crown” was considered treason, and therefore extremely risky by its very nature.

But, Crown Resistance Day, a violent day of revolution for Acton, arrived after a long series of prior events, beginning at least as far back as 1765 with the Stamp Act, along with the Townshend Acts and the famous 1773 tax on tea. In the years following, additional law changes, constraints, and taxes brought to bear by the British sovereign and government began to strain any remaining good will the colonies held toward England.

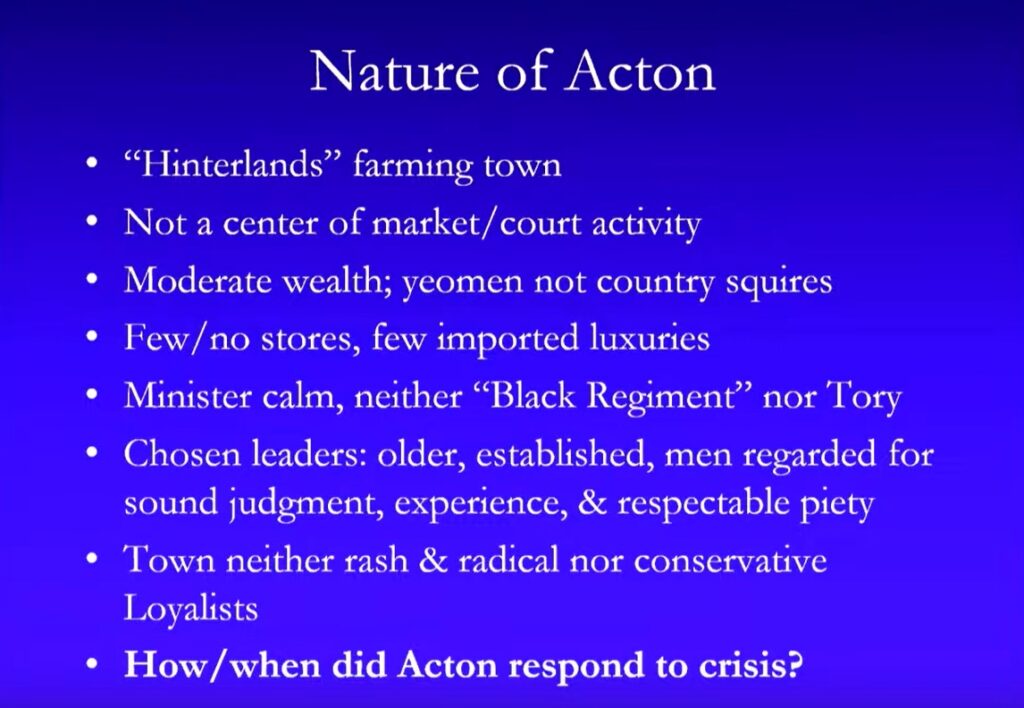

In that time, Acton and some nearby communities were almost entirely rural farming villages – yeoman societies – with less strong ties to Boston and to England. Thus, there was less interest in the politicking going on between Boston citizens and the Government established by the King. Acton, for instance, had little generational wealth, did not count many, if any, Tories (people loyal to the King) amongst its citizenry. Therefore, boycotting of British goods and services – which many Actonians could not readily afford – did not strongly affect Acton’s townspeople.

What did matter to Acton, however, was any perceived shifts to its well established way of life. Acton held regular Town Meetings to conduct town business, and these meetings were held whenever necessary. When the British government told cities and towns that Town Meetings could only be held once a year, that was a major blow to perceived autonomy. Likewise, when the government began to appoint, and more importantly, pay the judges in Massachusetts, that also struck a negative chord with colonists. Further, when the Provincial Congress was banned, that greatly riled many average citizens in Acton and across the Commonwealth, as it brought home a direct threat to their voices being heard and to their very way of life.

Fuhrer pointed out that Concord was in many ways similar to Acton, though it had more commerce. Groton, in contrast, had greater wealth, more Tories, and stronger ties to England, which differently aligned their local priorities, at least initially. No town could be called “typical,” though common threads of independence and self-governance had strong roots across most of colonial Massachusetts.

As more and more small towns began to understand the ramifications of England’s increasing pressure on the way of life for most colonists, the towns came into the fold of protest and thought of revolt. Most were eventually convinced to join together in both word and act, by sending representatives to a convention in Concord, a gathering that the Crown considered illegal. This protest by the townspeople of Acton was what was later called “Crown Resistance Day,” one of the most important events that led Acton into war, and a day that Acton has celebrated for more than 60 years.

The lecture was well attended by current Acton and Boxborough residents, along with the Acton Boxborough Regional High School Honors US History Class. A lively Question and Answer session followed Fuhrer’s presentation, with Acton’s Bill Klauer, of the town’s Historical Society, chiming in with some additional details.

The video of the lecture is available at Acton TV.

Kimberly Hurwitz is the Acton Exchange beat reporter for Acton250 events.

CORRECTION, November 18, 2024: In response to an email request from Dr. Mary Fuhrer, four edits have been made in the article to clarify matters of historical fact.