On April 10, 2024, the EPA announced the first federal enforceable drinking water regulations for PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), and placed concentration limits on some of these chemicals at 4 parts-per-trillion (ppt). The EPA predicts that significant health benefits will result from this action; however, managers of public water systems are discovering that compliance with these rules is both technically challenging and extremely expensive. The Acton Water District (AWD) is preparing to meet these new limits.

Contaminant limits for drinking water have been strictly controlled at the federal level since 1974, when the first version of the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) was approved. These regulations have been updated by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) multiple times and, in Massachusetts, its Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) applies additional water quality standards. Over time, allowable contaminant concentrations have steadily dropped from levels measured in the parts-per-million (ppm) to parts-per-billion (ppb).

The Acton Water District first deployed sophisticated water treatment technologies in the mid 1980s, when it installed equipment to remove trace amounts of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from its Assabet wells. This contamination was traced to discharges from the WR Grace facility, and the Water District subsequently obtained a $2.4m settlement to cover the cost of granular activated carbon (GAC) filtration. To ensure the quality of the treatment, the Water District established a local 5 part-per-billion upper limit on total VOC concentrations in the output water. At the time, this standard represented the most restrictive drinking water regulation for VOCs in the country.

The list of state and federal drinking water regulations has grown significantly since the installation of the VOC remediation facility in South Acton, and contaminant limits have become increasingly more restrictive. To comply with these mandates, the Acton Water District has spent in excess of $38m in the last 15 years to construct the North Acton, South Acton, and Central Acton treatment plants. Prior to 2020, all of the contaminant MCLs (maximum contaminant levels) that applied to Acton’s drinking water were above 1 part-per-billion.

Investigators in the field of environmental science have been concerned about the impacts of PFAS substances for at least two decades. These materials were first synthesized in the 1930s, and have been widely used in a variety of products because of their unique properties. There are thousands of PFAS chemicals, all of which share the property of having an extremely long lifetime. As a result of their widespread use and resistance to degradation, trace amounts of these materials have been found in almost every corner of the planet. In the United States, the two PFAS variations that have been most widely used are perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). Efforts are now underway to ban the US production of all PFAS products within the next decade.

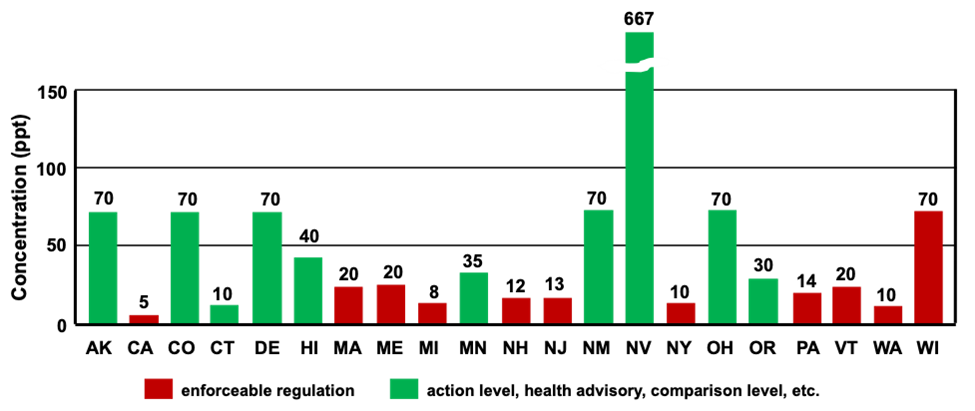

The regulatory landscape for suppliers of drinking water changed dramatically in 2016 when the EPA established an advisory level of 70 parts-per-trillion on the sum concentration of PFOA and PFOS. Although this was the most restrictive water quality standard that had ever been issued, the EPA was widely criticized for setting this advisory level too high and for failing to establish a legally enforceable regulation. Subsequently, a number of states enacted local regulations or health advisories. As noted in the chart below, the guidance issued by the individual states varies widely. In 2020 Massachusetts joined 10 other states that have enacted an enforceable regulation, and the Commonwealth set a limit of 20ppt on the sum of 6 PFAS chemicals (PFAS6). (As of this writing, only 21 states have established any type of advisory level or regulation.) While these directives have received broad support from the public and environmental health experts, water suppliers are now faced with the task of remediating a class of materials that their existing treatment plants were not designed to remove. Providers are also required to achieve levels of purity that are at least a hundred times more restrictive than any previous water quality standard.

Water suppliers in Massachusetts were only given a year to comply with the new PFAS regulations and, following the MassDEP announcement, the Acton Water District immediately initiated a set of short-term and long-term corrective actions. The raw water PFAS6 levels in Acton’s wells are generally in the range of 5 to 40 ppt, which is typical for water sources throughout the state. The short-term actions taken by the Water District include disabling sources that have high PFAS levels, mixing water from multiple sources, and reducing the pumping rates in some wells. These measures have been effective in keeping PFAS6 levels close to or below the limit set by the MassDEP. In parallel with these efforts, the District is pursuing long-range plans to retrofit each of its treatment plants with GAC filtration equipment. It is expected that these actions will reduce PFAS levels at the output of each plant to non-detectable levels.

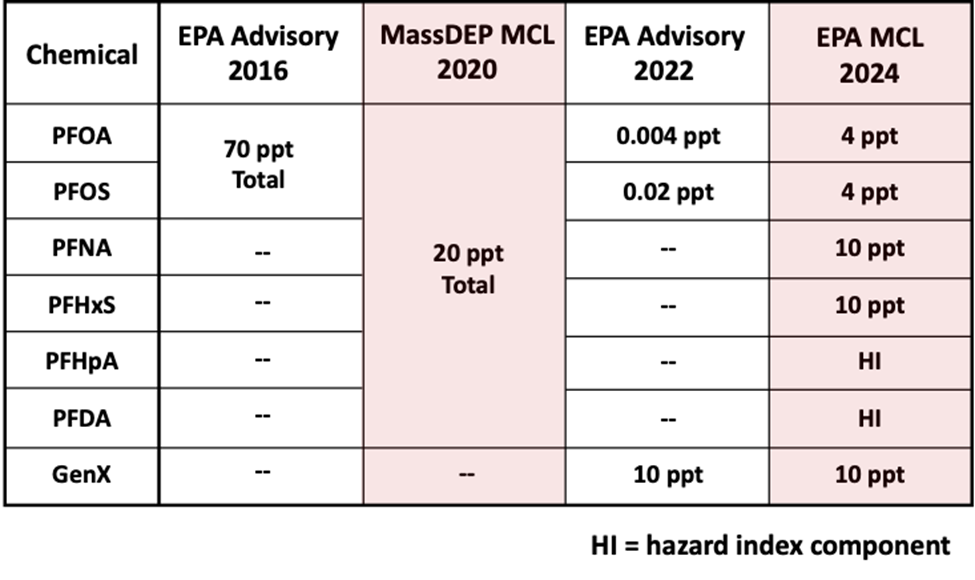

EPA’s direction on PFAS has evolved over time, as summarized in the following table. The health advisory issued in 2016 included the following statement: “To provide Americans, including the most sensitive populations, with a margin of protection from a life-time of exposure to PFOA and PFOS from drinking water, EPA established the health advisory levels at 70 parts per trillion.” Six years later the advisories for PFOA and PFOS were revised downward into the parts-per-quadrillion range, which is unmeasurable by current analytical methods. The recently announced MCLs of 4ppt for PFOA and PFOS represent the lowest contaminant concentrations that can be reliably measured at this time. Recognizing that these levels will be difficult to achieve, the EPA is requiring public water providers to complete an initial monitoring of PFAS levels by 2027, and be in compliance with the regulations by 2029. In the interim, water suppliers in Massachusetts must continue to be in compliance with the 20 ppt limit set by the state.

PHOTO: 2024_05_10_ActonWaterDistrict_PFASAdvisories_.png

To provide some perspective on the difficulty of achieving the 4ppt limits set by the EPA, it is noted that this concentration is equivalent to the ratio between a length of 1.5 millimeters and the distance between the earth and the moon. Contaminant concentrations this small are very difficult to maintain in a large-scale treatment facility. However, based on the results of preliminary tests using leased GAC equipment installed at the North Acton Treatment Plant, AWD Environmental Manager Alexandra Wahlstrom stated at the April 29 meeting of the AWD Commissioners that the Water District expects that the changes planned to comply with the existing MassDEP regulations for PFAS will also satisfy the new federal regulations. The cost to the Water District, and its customers, will be significant. It is projected that capital costs for treatment retrofits will be in the range of $20M, and the annual cost to replace and dispose of filtration media will likely exceed $1M. Expenditures required to comply with the existing PFAS regulations already consume a large fraction of the District’s annual budget, and the implementation of these corrective measures has substantially increased the workload on the District Manager and his staff.

There is some hope that State and federal funds will pay for part of the District’s expenditures PFAS remediation. Massachusetts has announced that $2M will be made available for grants and loans, and the EPA has promised to establish a $9B fund for financial assistance. However, given the number of communities impacted by these regulations, this money (all of which is collected from taxpayers) will only cover a fraction of the remediation costs. A more likely source of reimbursements for Acton are payments obtained from litigation against the manufacturers of PFAS products. Recently DuPont, Chemours, Corteva, and 3M have agreed to settlements that total in excess of $10B to compensate public drinking water systems for the impacts of PFAS pollution. The Acton Water District has retained the law firm of Napoli Shkolnick to obtain its share of these awards.

Looking further into the future, water suppliers across the country will need to reevaluate how to best comply with drinking water regulations that have now moved into the parts-per-trillion range. The economics of treatment at this level are not favorable, particularly since less than 10% of the water distributed to homes and businesses is consumed by humans. Climate change introduces a further complication, and regions of the country that experience extended periods of drought will face a very difficult set of choices. At least 21 towns in the Metro West region (including Acton) are currently considering a connection to the distribution system managed by the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA), which would essentially outsource the task of complying with water quality regulations to that agency. Irrespective of the choices made, Acton residents should expect to see the cost of water increase significantly over the next decade.

Dr. Parenti is a member of the Town of Acton Water Resource Committee and the Acton Water District Finance Committee.